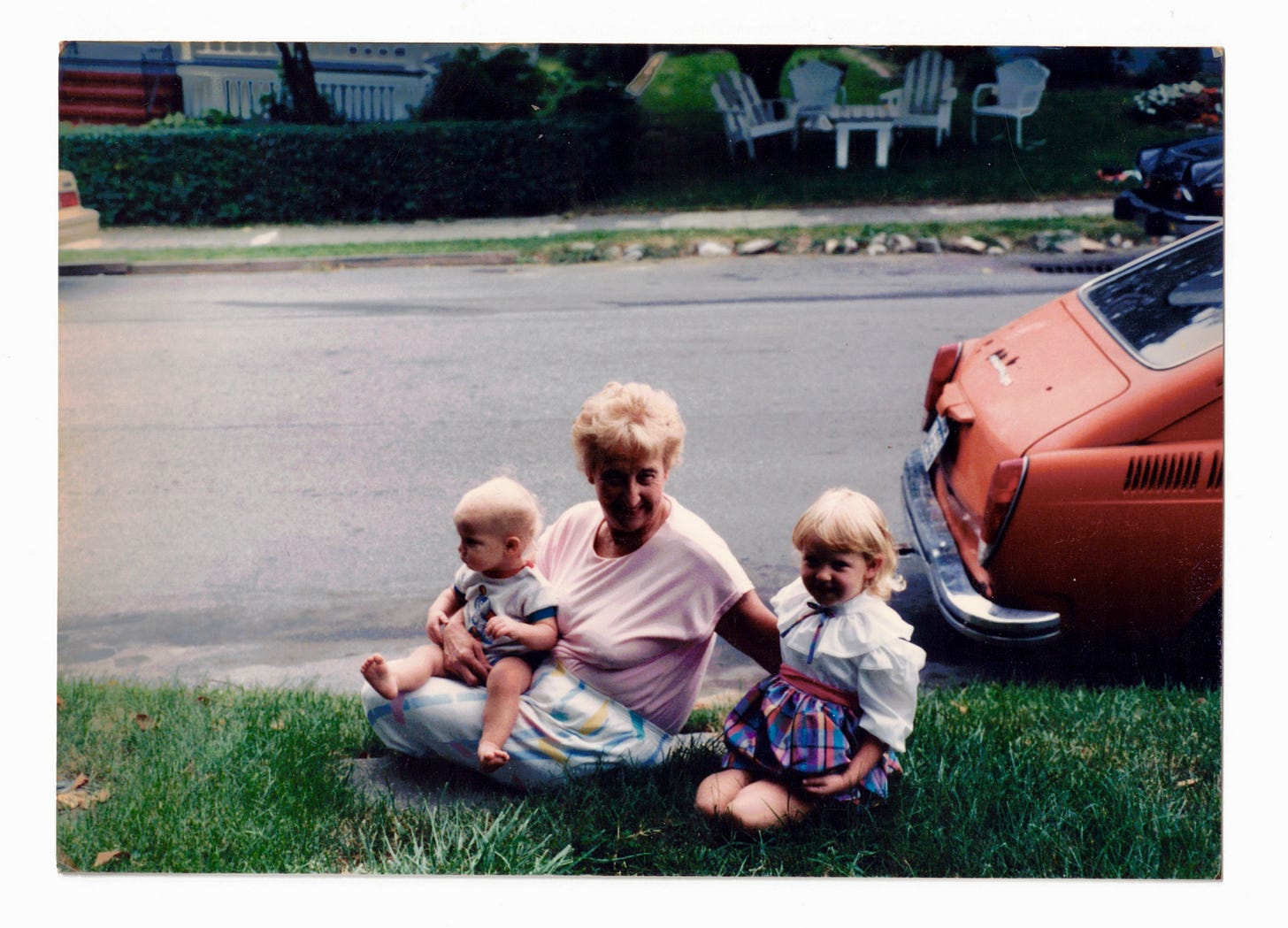

My maternal grandmother, Irene Joan Ruoss Hilton (better known to us as “Mee Mock”, which I guess my tiny brain thought was New England for “Mee Maw”), died 30 years ago on July 20, 1994 at the age of 68. I was just shy of 13. She had a massive heart attack. I was the one that found her.

Her death was a seismic event in my life. It is still difficult to wrap my head around how much everything changed afterwards, and how much she protected me from things I was too young to understand yet. I see now so clearly that she tried her best to shield us from the dysfunction of my parents’ marriage and whatever was wrong with my mother, her only child.

Irene was brassy, profane, intelligent, generous, hilarious, and kind. She had a ton of friends. She told me from the time I was little that your female friends will be the most important relationships that you have, and to treasure them the same way you would a marriage. She had her flaws, god knows. She was not a saint. She was just a woman.

I wish she’d at least been able to see me and my brother graduate from high school. I wish she had been at my wedding. Most of all, I wish I could ask her questions that I didn’t have the vocabulary to ask when I was a kid. Maybe those unanswered questions are just a way to hold her here somehow, and to hang on to the hope that I will see her again one day, even though I am not a big believer in the pearly gates.

I was going to write something new to honor her, but I decided to revamp an existing piece. It was originally published in an online literary journal called The Grief Diaries (which sadly shut down and there is no trace of it) in 2016, which was titled “Youth Dew”. What you will read below is an updated version of that essay. It still says just about everything I have to say.

I go over it again and again.

July 20, 1994. Wednesday.

The pool at the Trumbull Marriott. Swimming. Lawry’s Potato Stix. PB Max. Capri Sun. Afternoon. Hot concrete. Gin Rummy with my grandmother.

I draw a card and slam the cards down on the table in triumph. I have the winning hand.

I am from a family of foul mouthed sore winners, but I’m not allowed to curse yet, so the best I can come up with is a thing I wish I’d never said, that I spend my entire life wishing I could take back.

“DROP DEAD!” I exclaim, giddy with victory.

She pretends to flip me off and she laughs that laugh, that laugh I will never hear again but hear all the time, that laugh that twenty years from now will startle me out of sleep, will alarm me on the subway, will pop into my mind unbidden at the doctor’s office, at the post office, in line for a soup. I can hear it - sticky with cigarette smoke and chlorine. A guffaw, most unladylike.

She is what you’d call a “handsome woman”, Bea Arthur in a straw hat. Her skin is tanned and crepe, her upper arms baggy and soft. She is wearing a fuchsia colored swimsuit with white flowers and a ruffle on the bottom. Her cropped blondish grey hair is wet and her makeup has come off, except for a smear of bright red lipstick on her teeth, which also adorns her glass of Tanqueray and tonic. She smells like Estee Lauder Youth Dew and off-brand Virginia Slims. The last time I will see her alive.

After we get done swimming, we race to the car. I call shotgun. We wait for her - my brother, my friend, and I - sticky legs glued to beige pleather seats. Her beat up Pontiac K car. It smells like her. It smells like summer. We wait for her. Ten minutes? Fifteen? She doesn’t show up. Something is wrong. Something is very wrong.

I get out of the car and head towards the hotel lobby. Maybe she got distracted by something in the gift shop. When I get closer to the hotel, I freeze in place.

My grandmother is lying on her back on the pavement outside the front doors of the hotel. My brain springs into a protective action. Decades later, I still won’t be able to remember seeing her face, even though I know that I did.

I can’t run to her. I can’t take action. I can only stare, and scream. It’s a scream I don’t remember making, something that started before I was even aware of it, a scream that rose from a part of twelve year old me I didn’t know existed, some primal instinctual part. I can hear myself screaming but the horror inside me does not come out, despite the screaming, high pitched little girl screaming. Shrieking.

The horror grows. It fills every cell in my being, it becomes the stuff of my blood. It sings in my ears. An ambulance is called. I am carried inside, by a groundskeeper, kicking and screaming. Let me go. Let me help. I had just taken a CPR class so I can start babysitting, and I am confident that I have trained for this moment.

We are shuttled away from the hotel guests and put in an employee lounge while they call my parents. The staff has no idea what to do with three shell shocked children, so they offer us ice cream and anything we want from the gift shop. We used to beg for something - anything! - from that gift shop, but we turn it down. That’s not what we want.

My parents break the land speed record getting there, and I remember seeing them briefly before my mother rode with my grandmother in the ambulance to the hospital, my dad following. My friend’s parents come to get us and take us back to their house. They live across the street. We play SimCity and we build a new town, with a center park made of trees that spell out her initials. We swim in their pool. None of us know what to think, or feel. I certainly don’t realize this is the last afternoon of my childhood.

A few hours later, my parents arrive home. I run to them as soon as I hear the car door. As soon as I see their faces, I know. My mother tells me that my grandmother “went to heaven today”. She had a massive heart attack, and she was dead before she hit the ground. Just like that.

The shock is immense. It takes over everything. How can that be? She was just here.

And one fact haunts me, and will haunt me for decades to come—

I told her to drop dead.

And then she did.

***

At the wake, I am stoic. I see my grandmother in the casket, laid out in the rose colored satin dress my mother chose for her. Her waxen, hollow face is devoid of the person I knew. You can tell her eyelids are sewn shut. My mother holds her hand, strokes her hair, kisses her face. I want nothing to do with any of it. I touch her skin for one second and am revolted, horrified. She feels like cold, waxy plastic, with none of her familiar warmth or softness. My grandmother is not in that casket. She is somewhere else, a place where I cannot reach her.

I spend as little time as possible near her body. Instead, I hold court. I have grown up conversations with grown-ups, all of them impressed with my poise and intelligence. I am twelve going on thirty, they say. But I am not thirty. I am twelve, and I am traumatized, and that fact goes unacknowledged by anyone for far too long.

At the funeral, my mother falls apart, and never puts herself back together again. I look at my bereft weeping mother - the woman who has been both my favorite person and my worst enemy depending on the day - and I realize I am alone with this relationship now, a relationship that has been complicated since the day I learned to speak.

I know I should be crying, but I can’t. I watch, dry eyed, as the cantor sings Ave Maria and Pastor Karen talks about how much my grandmother loved us. I am dry eyed watching my mother weep into my father’s suit jacket. I am even dry eyed when the pallbearers carry her huge walnut casket out of the church. I pretend to cry so my mother stops asking me if I am okay. I am not okay, but I don’t want to talk about it with anyone, least of all her.

Two days after the funeral, I have my first anxiety attack. I wake up in the middle of the night entirely unable to breathe. My heart is bunny rabbit, my mouth is dry. The feeling is dread, the feeling is terror. It is absolute, all consuming. That was the first anxiety attack of thousands. The first time, but not the last, that trauma embedded itself in my cells.

A few months later, my grandmother’s Lhasa Apso, Pepe, hemorrhages to death on our kitchen floor, blood coming from his mouth. Our dog Toby – his brother – won’t leave his side. The vet thinks he ingested rat poison. It’s possible someone did it on purpose. My family is too grief stricken to pursue it.

In January of 1995, my grandfather dies after a seven year battle with scleroderma, a disease I would not wish on my worst enemy, alone in a nursing home. We always thought he would go first. My grandparents, who hated each other most days, had been married for forty years. In the end, they could not live without each other.

Twenty years or so later, I am sitting in my therapist’s office bawling into a Kleenex. The pain is exquisite, it is like someone is plunging a knife into me sideways and twisting. My therapist is quiet for a moment and just lets me cry. She leans forward in her chair and watches me, just nodding. She is not used to seeing me come undone in quite this spectacular of a fashion. This was The Thing I Didn’t Talk About, and here I was, reliving every horrible moment.

After giving me a minute to collect myself, she says, “The thing about grief that you can’t run from it forever. You have to go through the process. You can’t just skip it. You never grieved her. No one let you. But now you can. And it will hurt like hell, but it’s necessary. You have to grieve.”

My brother and I should have immediately been in therapy after she died, to process what we witnessed, but we weren’t. We were mostly focused on my mother’s pain. In fact, much of my life became focused on my mother’s pain. I had put her grief before mine. I had put her suffering before mine. Now that I was focusing on my own trauma, I could no longer run from the crushing, pounding, blaring garbage truck of crippling grief that barreled over me. I had no distraction from it.

How could the pain of something that happened more than twenty years ago be so fresh, so raw? It was as if I was twelve again - vulnerable, scared, confused, and guilty. And hurting - hurting so deeply - from the loss of one of the only people I can say loved me unconditionally. The person who bought me my first typewriter and my first watercolors. The person who taught me about the wonders of whole belly fried clams and chowder. The person who let me talk her ear off for hours and hours. The person who watched The Golden Girls with me and put Vicks VapoRub on my chest when I was sick. The person who taught me how to love, and how to be loved. And she was gone. She had been gone for so long that I started to wonder if she had ever really existed.

And there was still that tiny part of me that was afraid it was my fault. That I told her to drop dead, and then she did.

***

Not long after this therapy session, I have a vivid dream. I am on the steps of my old house, and my husband is there, and some weird dream stuff happens that I can’t quite remember. I look across the street and both my late grandparents are in my neighbor’s yard. They are hugging my mom and my dad and my brother. I run across the street, unbelieving. They are ALIVE! Alive, in front of me! My grandfather hugs me, and he is so frail and bony, like he was before he died, but so happy to see me. Then I turn to my grandmother, who folds me into her arms, and for the first time in more than twenty years I can clearly see her face. I hear her voice. I feel her skin. I smell the Virginia Slims and Youth Dew. It is in this moment I know that I am dreaming, but I don’t care.

Suddenly, we are at her house, as if by magic. She invites me into the kitchen, the one I grew up in, with the yellow patterned wallpaper and roosters on the oven mitts and hand towels. She starts to make dinner and offers me a gin and tonic. I accept, happily. She makes it strong, with Tanqueray in its iconic green bottle. She lights herself a cigarette, and one for me. I really hate menthol, but I don’t turn it down. I am afraid any rejection will end this visit, this visit I’ve wished and hoped for. Her lipstick stains the filter. I inhale.

“You’re all grown! How old are you now?” she asks me.

“Almost thirty-four,” I tell her.

She throws her head back and laughs. That laugh! No longer a phantom – I hear it. It rings my eardrums. It swells my heart. I choke back tears.

“Well!” she says, taking a thoughtful drag, “That ain’t old, but that ain’t young either!” She laughs again. I realize that I am almost exactly half the age she was when she died. She asks me about my career, my husband, my apartment, my friends, my life in New York. It’s an easy conversation. There is no sentimentality, no “oh how I’ve missed you”, just two grown women getting drunk on gin and tonics and making meatballs, as if we did this every week.

A thunderclap. Lightning.

I wake up. I’m in bed. There is a storm raging outside. My husband sleeps next to me. And I am furious. I wanted to tell her I was sorry for telling her to drop dead, for not doing CPR, for not being able to make my mother well. I wanted to tell her how much I loved and missed her. I wanted all of these things and I didn’t get to say them.

And then, a realization: I didn’t have to. She knew.

Grieving my grandmother was a painful and revealing process. I did not realize how much my avoidance of this grief affected every aspect of my life. I had been carrying this around with me for so long that when I finally was able to put it down, I felt lighter. It’s not that it doesn’t still hurt – it actually hurts more, in its own way - but that pain isn’t something I have to run from now. I can acknowledge it, feel it, and let it go.

I was able to forgive that little girl who felt like she was somehow responsible. I knew intellectually it wasn’t my fault she died. My mother told me she was supposed to get her pacemaker checked, and as usual, she kept putting off her doctor’s appointments and the damn thing malfunctioned. Still, I felt like my words had power. It took a long time to emotionally understand that a twelve year old girl has precious little power in this world, let alone in matters of life or death.

Even though she was only in my life for twelve years, my grandmother’s encouragement and nurturing of my creativity had a huge impact on my future. I found out after her death that my grandmother had aspired to be an actor, and had a scholarship to study theater in college. Her family would not allow it, and she did not go to college or pursue theater at all. She never mentioned this to me, but after her passing, I threw myself into the theater with passion and determination. I began writing plays and acting in earnest, driven by a force I could not identify.

I don’t know that I believe in any kind of afterlife, but if there is anything resembling a spirit, I am convinced that a part of hers became a part of mine that terrible July day. Everything I do in my artistic life is in honor of her. I do this with pride and a sense that, in the end, I did right by her. It is without question something she would have wanted.

Because she loved me. And shouldn’t we all be so lucky?

an addendum:

I was at best ambivalent about Taylor Swift, until I heard her song “Marjorie” from her 2020 album Evermore. As it turns out, she lost her grandmother when she was around the same age I was when I lost mine. Marjorie was as profound an influence on Taylor as Irene was on me. I don’t think I will ever get through the whole song without crying.

All your closets of backlogged dreams

And how you left them all to me

I had no idea I'd cry so hard thus morning. This is so beautiful. The descriptive details made it feel like I was in the scene at times. And my heart broke so hard for 12yo you, and for the decades you experienced after. Thank you for sharing.

Oh, I love the song “Marjorie” and never knew it was about her grandmother. Thank you for this piece and for sharing Irene with us.